Ben Tousley on designing timeless album covers

Ben Tousley designs album covers based on a feeling.

He’ll scan a folder of images while preparing a mood board for an artist, setting aside those that inspire him. He’ll work with artists to identify visuals that match the emotions behind their albums. And he hopes his album covers will elicit that same emotion from the listener, as they hold the record in their hands or glance at it on their phone’s screen.

“It’s very meaningful, important content that [the musicians are] putting their heart and soul into,” he said. “The album cover is a big part of how people will experience that for the rest of time.”

Currently based in Marseilles, France, Tousley has been in the album cover design business for almost two decades. For indie rock fans, his work is easily recognizable: He’s designed iconic covers for a number of the genre’s heavy-hitters, including Grizzly Bear, Fleet Foxes, and Rostam.

Tousley is also the founder of Buds Digest, a magazine for queer stoners, and is an Art Director at The New York Times’ branding and audio department. His graphic design work across all three mediums isn’t isolated — one informs the other, which influences another.

We spoke with Tousley about his unique approach to album art design, what it’s like to consistently collaborate with an artist over many years, and why he finds it rewarding to mix up the work he creates.

Did you know that you wanted to work within the music industry at a young age?

I think I did. My first significant job ever was working at a music store in Indianapolis, IN called Luna Music. It sold CDs and vinyl. I’d go in there all the time and it was the coolest place in the world, with the coolest people. I was discovering things that blew my mind all the time and they asked me to work there. I think they could tell I was a big fan. It was kind of community-based and I met so many great people and discovered some new things.

Photo courtesy of Ben Tousley.

Fast forward later, I started working with Grizzly Bear. We were connected by the internet through a music website. I don’t think I could’ve ever sat down at a young age, or any age, and been like, I would love my career to be what it has been. I think that it would’ve been audacious to assume that I could’ve worked on so many amazing records for such a prolonged period of time. I feel very grateful for that.

How did you make that jump, from working at Luna Music to designing for Grizzly Bear?

It was the dawn of the internet and I had a website where I was putting up drawings and illustrations and photography. There was a website called Audioscrobbler, which was also known as Last.fm, where you would track what you were listening to. It was kind of like a social network. I don’t know if it exists anymore, but that’s how I got connected to Ed Droste, the singer of Grizzly Bear, and we became friends.

It was a friendly relationship and he was sending me demos for the record. I think I basically was like, I have to work on this. When I look back on that, it felt like a complete fluke. I don’t really know how that happened, but there was cool momentum and energy getting to hear Yellowhouse. He’d send me demos for that and they were shopping around for labels and then all of a sudden, it was kind of a snowball, crazy thing that happened. And now we’re here. It certainly was a pivotal moment. If it was another record, it would’ve been a completely different experience.

What album cover inspired you to start a career in this?

I love album covers and that period of working at the record store. I have so many things I thought about for your project, and it was a difficult and fun task. The visuals are a direct link there, for the things I love. Certainly, I don’t think there’s a single album that’s changed my life that I didn’t also love the artwork for it.

I’m a huge Radiohead fan. Kind of obsessive. I know I put a Radiohead song in there, whatever the first one is that sparked it all. I was 15 when Kid A came out. That was the peak, perfect time to have that shape my life. And the music and the video and the visuals of it really blew my mind. They would do little short videos in the era of MTV when there were music videos. They would do little 10-second commercials that would air in between music videos and they were really weird and kind of creepy. Those were my favorite music visuals of anything I’ve ever seen. They were called blips and they were really cool.

Is there something like that now?

I think Instagram is that. In a way, people make shortform video all over the place and I think [Radiohead] really was ahead of its time in that way. Though I don’t know if people use it as artistically as they did. The experience of it was really disorienting each time you would see it on the TV.

It was shorter than a normal commercial too and it would have their weird music playing too. It felt very anti-commercialism. It was like a weird, subversive, intriguing thing rather than “Here’s our new product and you could buy it at the following three places today.”

When it comes to process, how do you first approach album art design?

It’s really different each time. A lot of the time, artists and musicians will have an image already; they’ll have a scrapbook. And then sometimes, they have no idea and they don’t know what they want it to be, but they’ve spent years working on this music. They might have the vocabulary for talking about visuals, but aren’t sure how to go about it. Or it’s just not their cup of tea at all and they just don’t know what to do.

I think it’s important to familiarize myself and immerse myself in what the music sounds like, find out what the most exciting moments are for me, and then talk with them. Oftentimes, if they don’t know and we have to start from a blank slate, it helps to start a dialogue and talk about what kind of visuals we do like. It doesn’t have to be visuals for this record, but let’s talk about book covers and record covers and movies that you like, just so we can start getting a sense of their taste in the world and the world that they’re trying to have their work exist next to.

But sometimes, like Crack-Up for example, Robin [Pecknold, the singer of Fleet Foxes] knew that photo already. He’d done layouts for the tone. When we started working together, it was me helping iterate and figuring out the best ways to turn this into a structured thing that would fit all of the information.

The album cover for Crack-Up by Fleet Foxes.

With Shore, there was an interesting concept that he had. Robin had so many amazing references for that record, all of these Brazilian covers, and just so many cool, vibe-y things. We set out making with another artist and collaging on our own, making our own vibe-y stuff. It ended up coming all the way back to the same artist who did the image we used for Crack-Up, Hiroshi Hamaya. That’s another example of “Who knows? It’s all over the place.”

Getting into the logistics of designing the art, you’ll talk to the artists about the art they have in mind or you might start from scratch. From there, where would you go?

It’s usually a big folder, a presentation, a moodboard of sorts. It’s just casual, looking at stuff. In doing this for a while, I have a large bank of things that inspire me and types of imagery that I love. Sometimes what I’ll do is, after we have some conversations about things that they like, things that are important to them about the album, I’ll listen to the album and search for certain things in mind. Like, “I really want it to be an energetic shot of the ocean, but I don’t know what it is and where it comes from.”

Because, to step back, at the beginning of all projects and the end of it, it’s logistics. Well, what is the image? Where does it come from? Are we allowed to use it? Can it be accessible or do we have to make it ourselves?

I’ll go through this big folder that has thousands of images in it, but I don’t have them organized. I just kind of go free association with it and see what pops out at me. Usually, I’ll start to pull those. It’s a very fun task to take a big set of possible variables and see which one’s telling you they want to be considered. Then I’ll share that with the artists and depending on how they respond, like if there’s something in there that’s like, “Oh my God, that’s incredible,” then that says to us, should we try to make this ourselves? Should we try to track down who made this and see if we can get access to it? Should we pivot off of it somehow? It starts to answer those questions.

How long does the process take?

That also does not have a definitive answer. Wherever the wind blows.

For example, with Shore, I think it was 2020? Things were bad and it felt like there was a timeline in the air where we felt like we had to finish this as soon as we can. It needed to happen for everyone involved and for [Robin]. Getting it out there and the work felt like a gift and a reaction to a lot of things that were happening in the world. That was fast. But often, labels want to have it done many months before it comes out. Sometimes six months to a year. It’s a lot of hurry up and wait.

The longest record that I worked on took probably six months to a year. The shortest versions might be three months. If everyone’s got everything ready and it’s good to go, and people can make decisions and be at peace with making decisions, it can be fast. But if not, or if there are a lot of people involved who don’t agree on something, then it can take longer.

Some of your album covers are photo-based, and the photos are captured by another person. Are they usually commissions or do you pick something that already exists?

That also varies. Oftentimes, I feel like part of my wheelhouse is pairing things that might exist with music, or at least with the more successful ones. There are commissions there too. I enjoy that and I feel like I’m at a place where I have a body of work I can reference.

The album cover for Pulse/Quartet by Steve Reich.

I’m not an art director who has a point of view or a character to my work. I really try to work with the other person and try to be a chameleon in my presence of it, as long as I think it works for the music. This is a long way of saying that I’m not sure I’m very good about commissioning and art directing in a way that is direct. If I get to a point where I’m commissioning with an artist, it’s because I really like their work and I want to defer to them. Again, it’s all over the place and there are already so many things that exist.

How do you interpret the photos themselves in order to match the vision of the artist?

It’s an interesting mix of ingredients that go into what makes it “good.” That includes the cover, the tone of the music, the subject matter of the music, and the title, often, is really important. In a lot of ways, I’m reactive towards that. What will be an intriguing pairing with that title? What would make you think?

The album art for Cook Up by Sam Gendel.

We live in this digital world where things have to be beautiful when really big, and also when they’re really small. What would be immediate, or if not immediate, at least intriguing, or ask you to look at it again? Those are all factors that go into it.

When I describe it to someone whom I’m working with for the first time, oftentimes I’m just like, “Well, we’re just going to look at a bunch of stuff together and then we’ll start to feel it when it feels right.” We’re all students of visual language because of the world we live in, so we all have an opinion of it. We’re all consumers of visuals and really, anyone could do this. It’s all subjective, basically.

In the dialogue I have with the artist, it’s identifying what we’re feeling. It feels good. It feels right. It often gets to a point where this has been it for a long time. Or this was supposed to be it the whole time. It unlocks it and grooves, but there’s no real metrics other than a feeling, which is kind of lame.

Is there a difference between working consistently with one band for years, versus working once with an artist for one album?

Oh, yeah. I love working with people on repeat occasions. I love the world-building of all of it. I love thinking of things in succession. If we did this last time, what if we did something else the next time? Not necessarily being reactive to be reactive. It has to be appropriate for the record.

With the repeat people, you get to have a bit more of a vernacular together. You get to be comfortable together. Oftentimes, with one-offs, you’re getting to know each other and maybe you’re not sure if you trust each other or trust each other’s judgments. You have to feel that out and build that up. Not that I’ve ever had any problem with that, but I do think, with record covers in particular, you’re talking to people who’ve worked on these records for years of their life. It’s very meaningful, important content that they’re putting their heart and soul into. The album cover is a big part of how people will experience that for the rest of time.

I say all of this to say that I appreciate when I can work with people multiple times because A, I think there’s a trust there and B, it’s fun to expand the world in ways of, where can we pivot or not? Can this be a series? I’ve worked with Caroline Shaw, a composer, quite a few times. I think I’ve worked with her more than I’ve worked with anyone else at this point. If you look at the covers I’ve done with her, there’s a series that’s starting to happen throughout them. It’s fun to use restraint in that way, to be inventive for the new stuff.

The album cover for Evergreen by Caroline Shaw and Attaca Quartet.

It feels like a true partnership over the years.

Yeah, I think so. It’s interesting, with Grizzly Bear, I was so young. I owe so much to them and I feel very grateful to them. It all happened so fast. It feels like a dream, to look back and be like, I guess I was a part of all of that. I did a lot of visuals for them and I also did ads for them, more marketing than I usually do. It’s interesting to look at now.

They’re incredibly important people in my life. I have a lot of great love for them over time. I would love it if everybody I worked with was a repeat person, but of course, it can’t be. Some people like to mix it up and give themselves challenges, working with different people, or they want a specific thing I don’t do.

I can kind of guess the answer to this. What is the most rewarding thing about your album design work?

I would love to hear what you guess.

Your answer just now, building these relationships with these artists and being able to create such a tangible thing that you can flip through. Being a part of something that people can touch and feel and create a part of an overall album experience is so amazing. What’s your answer?

Those are all great and absolutely true. I’m a huge music fan. It’s God’s breath on the planet, that we get to have music and enjoy it. Anybody who makes it or dedicates their life to it, these people who write music that has affected my life and other people’s lives — getting to have a rapport with them and being a part of the process, seeing what their process is like, that is a gift. I love that.

Like you say, being a part of something that may outlive myself or affect people’s lives in that way, in a tangible sense, that’s an incredible gift. When I think about the relationship between myself and people who are making stuff, it’s inspiring to feed off of each other, be creative, and be pushed together to make something good.

What’s the most challenging thing about working in album design?

The album cover for Mélusine by Cécile McLorin Salvant.

I think the most challenging times I’ve had have been when people didn’t agree or didn’t trust each other. It made it so the dialogue was difficult. That’s been the most challenging and that’s happened with all sorts of artists at different stages of their careers. Who knows why that happens?

I would say that, and trying to keep up with trends, which I pretty much swore off since day one. I want to make something that feels timeless and true to my interests, but I do think that it being a career, it’s kind of rare to otherwise be successful in it if you’re not super trendy. For anyone who’s trying to get into it, ignore that. Just do what you think looks good and beautiful, and be true to yourself in that way.

You not only design covers, but also the center labels, inserts, and the interior of the album. How do you consider a person’s interaction with these tangible things when you’re designing the album experience?

It’s all an extension of the world of the cover. The cover is what we prioritize and it’s hard to work on the rest of it until that’s locked in. The way I think about it is almost reactive. If that’s the cover, what’s it going to feel like when you flip it over? An element of surprise or something? It’s this beautiful, cool opportunity to extend the experience and the feeling, and have it be surprising or exciting that you’re seeing more of it.

Honestly, I wish that I was experimenting with some of that stuff, but a lot of times, that’s where the legal information goes. That’s where the credits and the names of people go, so it can be kind of a strict place to get really silly or playful with. Of course, it’s not fact and I can probably push that. It would be fun to push what you can put on a center label.

For me, I think about it mostly in terms of what’s the appropriate extension of that world of the cover.

Album elements of Shore by Fleet Foxes.

I remember opening up the Shore album and finding the poster inside, and was pleasantly surprised!

That record has a lot of special tricks in it. Those are things Robin knew up front that he wanted to do. Maybe not up front, but those were his ideas. We knew we wanted to do an etching, but what was it going to be? We worked on that together. There’s a lot of beautiful, deluxe stuff in the standard version of that record that is really, really cool. Even the board, the way that it’s printed, is called paper over board. It’s thicker, more cardboard-feeling, which is more of a classic, old approach, printed by this amazing place in California that does the best version of that.

On the flip side of all the tangibleness, do you ever consider how your work translates on digital music platforms?

Oh, yeah. Since Grizzly Bear, I’ve always considered that. Maybe Yellow House isn’t the best example of that, but you can see that much later in Veckatimest and Shields. Thinking about, is this going to be beautiful, big and small? Aside from that, I’m not a Spotify user myself. I use Apple Music because my CD collection transferred over to that.

It’s a fun challenge to think about the scale. And oftentimes, that can be kind of a disregard. “Well, what does it matter if it looks bad when it’s small?” But does it make you want to make it bigger? Do you want to look closer when it’s small? It’s a fun game to play.

You’ve built these worlds with artists. Having to translate them to less than 1080 by 1080 pixels, I would think a creative might think, “Ah, I don’t really like it.” I love your answer though. It’s part of our world now and there is something to squinting at an album cover and wondering, “What is that?”

It might seem like for a designer, it would be less fun, but the cover is everything. And you’re still, in some cases, depending on how your phone is interfaced, you’re taking up that person’s screen and you’re creating the vibe. You’re directly in the pocket of wherever the audience member is. In that way, it’s incredibly important real estate, regardless of the size. In many ways, it’s more direct than a vinyl or a CD ever could be because you’re on the phone on the subway. It’s there with you wherever you’re going. When you want to listen to the album again, you have to look at the cover again.

In that way, I think there’s a lot of power in it. The scale is a fun, module design, a nerdy thing to enjoy. I think about it that way, as a system or something. Almost like designing wayfinding for a building. Can you read this from really far away? Does it still have the same effect? Is it recognizable? I enjoy that a lot.

How did you get started in The New York Times’ audio branding department?

When I first got into knowing what graphic design was, it was through journalism. I was in journalism classes and we had to design our own sections of a magazine or a school paper. I realized that between writing and layout and design and typography, [graphic design] was the skill that came more naturally to me. Instead of going to school for journalism, I ended up going to school for graphic design and pursuing that more.

Fast forward to living in New York and the first time I worked for The New York Times, I worked for The New York Times Magazine for a very short period of time. That was a really amazing experience. They’re an incredible, small team. Really ego-less and really incredible design challenges and content. Kind of working with the best of the best. That was a quick, short taste and I wanted to explore more of that.

It was over some years that I eventually got connected with someone in that branding department who liked my work a lot and continued to engage me for work. It’s been one year of my existing version of that role and it’s been cool.

With it being such a new, big department for them — audio and all these podcasts — I think the second round of work I’ve done is getting engaged with these podcast covers. Again, the art of the square and the scale — it’s the same exact thing as an album cover. It’s been a cool experience to see the app and the way it’s been growing since then. It’s an interesting time for journalism and the way people receive information.

Do you dabble in any other art form besides graphic design?

I do. I love taking photos. I take a lot of photos with film, just kind of shitty cameras, and that’s been fun for me, always. And also I make my own music. I used to make music a lot in high school and college, and I stopped when I moved to New York. But in the past couple of years, I made some big life changes. I missed that feeling. I started that again and it’s been very rewarding.

Covers for Buds Digest, the magazine Tousley founded.

I also run a queer magazine. I’m about to publish a new issue this month.

Has it been rewarding, juggling all of these different art forms at the same time?

Somebody asked me the other day, would you recommend that people have to do that many things to get a rewarding feeling? I would say no, but it is rewarding for me. I think it’s allowed me to mix it up. I sometimes have a low respect for graphic design. I’m not dissing it as a career path — at a certain point, it’s color, it’s shape, it’s very basic stuff. It’s an infinite amount of solutions, but also kind of finite. It doesn’t matter. It’s kind of superfluous. It’s the sugar on top of the cake you’re eating. It doesn’t matter either way. It’s not changing the world.

To combat that, mixing it up for me was really healthy. Scratching different itches. I worked for The New York Times Magazine, and I told you the whole thing about how I wanted to work with them again. After that period, with another friend, we were like, let’s just make our own magazine. That way, we can have the experience without someone giving me permission to do it or telling me I’m good enough to do it. Just do it. That whole ethos really changed my life in the last couple of years.

More than feeling like I have a lot of different stuff I’m doing, I’m feeding my curiosity with it. And that’s what’s rewarding. I’m not sure if it’ll all keep spinning at the same time. I might put one down and never pick it up again, but it’s fun to try different things and to see how that informs my practice of graphic design. It invariably will morph what’s possible once I see that I can do it myself. Anybody can do anything.

One of the things I’ve heard about musicians is like, David Bowie didn’t just come out and make a record that sounds like it’s from outer space, out of nowhere. It has ingredients from things he was mimicking from things he liked from his life. I think about that when I’m trying these extracurriculars because it’s like ingredients you put in a soup. The more you do that, that’s how you create your unique point of view. We’re all just doing that. I don’t think anybody’s truly original. People are just mimicking what they like.

I’m trying to pick up that energy myself and find my own unique combination of those ingredients by expanding the palette.

. . .

Here are Ben Tousley’s 12 songs.

“Today” by Smashing Pumpkins

Smashing Pumpkins started it all for me. I needed every release I could find, poured over the artwork, and covered my life with them. I remember the feeling of watching the music video for this song on VHS and the glorious, horrible, dawn-of-the-internet quality like a kid learning other worlds were out there.

“Let Down” by Radiohead

Around the age of 13, my dad took me on a trip to the big city of Chicago for the first time. I had some CDs that my friend's older sister had lent me, including OK Computer. There’s no downplaying what a huge Radiohead fan I would become and the ways I’ve absorbed it all. And that harmony at the end never fails to ignite the same feelings as it did then. On the same trip, my dad also picked up a copy of Neil Young’s Decade compilation. Between the city and these sounds, it was quite a formative experience.

“The Moon” by The Microphones

This is one of those songs that feels so vital that I can’t imagine it not existing. The Glow Pt 2 was huge for me in validating my feelings as a young person in the suburbs, confused and astounded by the natural world just beyond our mundane parking lot life. This song epitomized that feeling. That Phil Elverum has a full, still-growing catalog of many such epiphanies is a gift and his career has really taught me about the beauty of a continued art practice focused not only on making but also pointing the interrogation back on ourselves.

“Colour Me In” by Broadcast

Like freefalling in a dream, there are so many things I love about Broadcast. This entire album Haha Sound ignited such excitement in me for the gorgeous possibilities of strange sounds and landscapes in music. They’re just the greatest to ever do it and I can turn to them any time for that jolt of inspiration and beauty.

“Easier” by Grizzly Bear

Difficult to understate how much Grizzly Bear has influenced the course of my life, but the thrill of getting to hear this music as it was being created definitely changed me. They felt like a remembered combination of everything I had been interested in in music at that point, piped in from a dream. It sparked my mind in such vivid visual ways that it still continues to power this curiosity I’m grateful to practice.

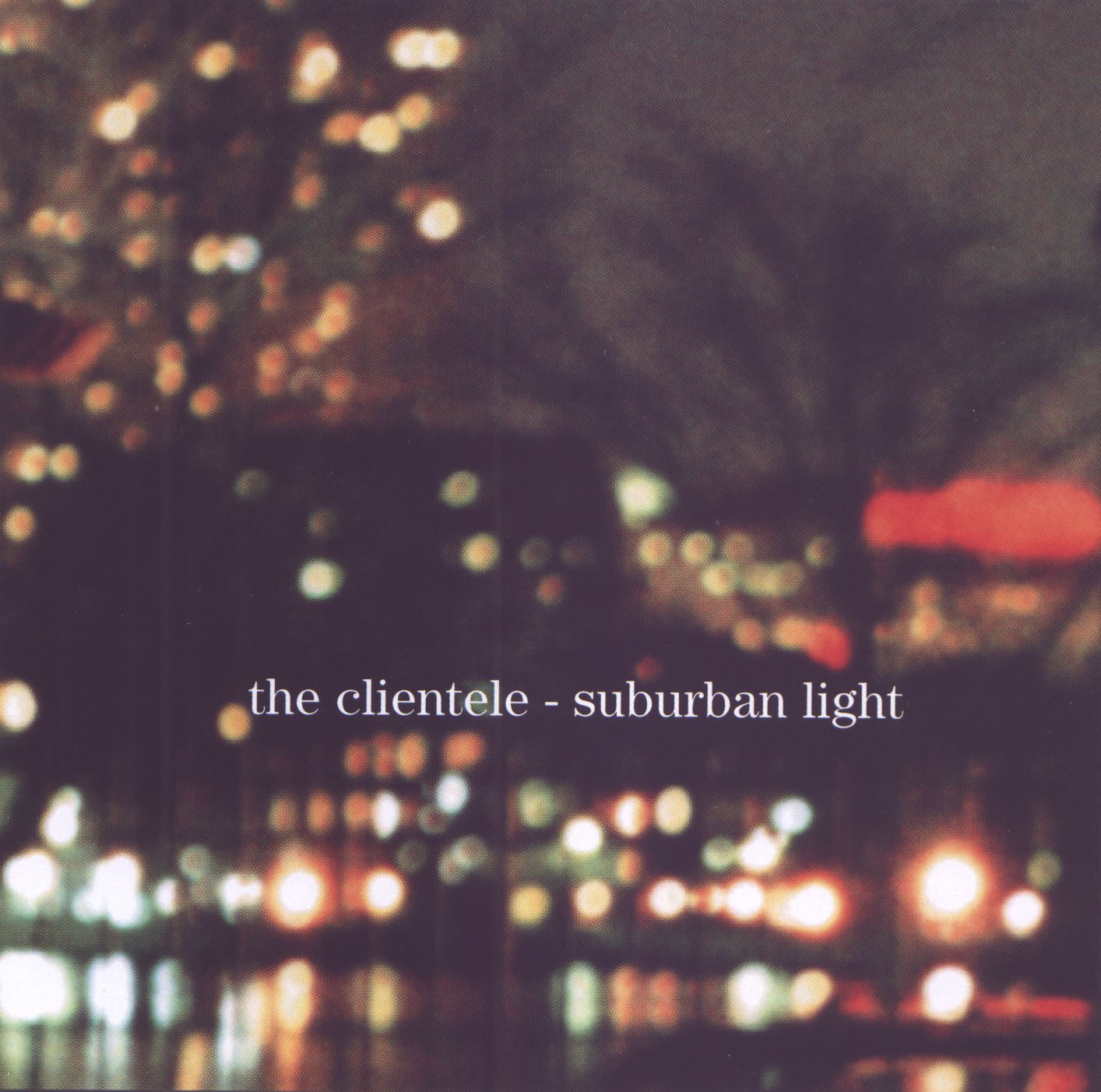

“I Had To Say This” by The Clientele

Another all-time group for me that I can happily say I remember when I heard it for the first time. I had the pleasure of working at a local Indianapolis record store during my high school years. A lifelong friend that I made there (shoutout to John!) recommended I try The Clientele and I can remember the feeling of the warm spring air as I blasted this on the speakers with the front door open. Every song from their catalog always takes me to some similar nostalgic memory.

“In A Beautiful Place Out in the Country” by Boards of Canada

Boards of Canada were the first electronic group I ever got into. Looking back on it, I’m not even sure I could understand what it was that I loved about it other than its strange, hypnotic world left me with a new feeling. Thinking on it now, after many years of loving them, that mysterious, hypnotic quality endures.

“Soon-To-Be Innocent Fun-Let’s See” by Arthur Russell

I can remember exactly the moment I heard this album, sitting on the floor of a friend’s dorm during my freshman year of college in 2005. I wish I could package that feeling and give it to people. It sounded nothing like I had ever heard. I had not yet come to terms with my sexuality and falling for Arthur’s music coincided with finding that strength for me. The music and its story resonated as a precious artifact, something important that I wanted to hold dearly and carefully. Going on to learn and hear so much more from him over the years has only solidified my love for his creative world. Arthur Russell forever.

“Cloudbusting” by Kate Bush

What to say of the life-changing ways of Kate Bush. “Cloudbusting” was the first of her songs that I was recommended (shoutout to John, again) at an age where I was shocked that I hadn’t heard of her yet. This was around the dawn of Youtube and social media and I remember my friends and I devouring her videos like kids at the candy shop. It doesn’t get better than the lightning strike of Kate Bush.

“Didn’t Cha Know” by Erykah Badu

Erykah was my entry point to the life-affirming power of bass and repetition in all its various musical forms. I got into her around the release of New Amerykah, Pt 2 as I was 24 and just living on my own for the first time, enjoying the freedom of playing music in the house at loud volumes.

“Small Hours” by John Martyn

I’ve long had an affinity for folk music and anyone who can spin its traditions into exploratory territory. As I got into John Martyn, a video of him performing this song at Reading University in 1978 really did a number on me and it still does. I was experimenting with recording acoustic guitar at the time and the way he conjures this immersive, boundless world both inspired and made sense to me – like that’s what I wanted to do, too. That personal inspiring element aside, there are few more heartbreakingly, beautiful and empowering songs to me.

“Thymia” by Fleet Foxes

Fleet Foxes have been blowing my mind since day one and there have been many life-changers along the way, but this album Shore came at an important impasse in my life. It’s a collection of such warmth, but this song particularly crystallized a moment for me and felt like a mesmerizing balm for the pain of reckoning with where I was and where I wanted to go. There’s a mysterious power in its simplicity while worlds pour out of the harmonies.

Listen to Ben Tousley’s curated 12 Songs playlist below.