Hanif Abdurraqib opens up

Hanif Abdurraqib’s voice is warm when he tells me about his love for Ohio. He talks about how grateful he is to live in Columbus, what a privilege it is. And when he’s done singing its praises, I feel like I love Ohio too, even though I’ve never been. That’s what it’s like to read his writing.

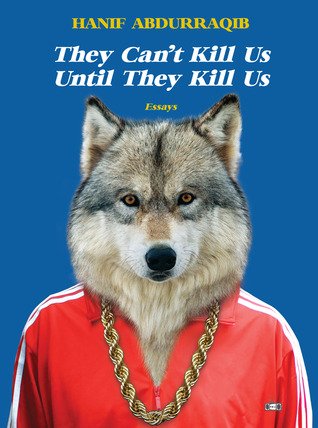

Abdurraqib is an essayist, poet, and cultural critic, published by an extensive roster of publications. His first book, “The Crown Ain’t Worth Much,” uses poetry to tell moving narratives, and his second, “They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us,” is an anthology of essays that unravel music and the memories bound to it. Both are deeply personal works of prose.

. . .

When I first read Hanif Abdurraqib’s second book, I was stunned to see how open a person can be about how he connects with music as a black man from Columbus, Ohio. He writes about being the only black fan at a Bruce Springsteen concert after visiting Michael Brown’s grave the day before, losing his mother and best friend, and appreciating the comfort Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright” brings to the black community. As an Asian-American woman from New York City, I didn’t think I could ever empathize with what he’s been through. But the beauty of his work is its specificity — the more detailed the story, the more relatable the elation, frustration, and grief.

I’m so entranced by Abdurraqib’s description of Ohio that I realize soon after that my recording app didn’t capture any of it. I manage to catch the last sentence he says about his home state: “I wanted to give back.” As we continue our conversation, it’s evident that this desire to reciprocate all that something — whether it be a city, music, or his readers — has given him is what drives him.

Here’s the rest of our interview, edited and condensed for clarity.

How did you get into writing poetry?

Weirdly enough, the thing that my music criticism is sometimes praised for now and wasn’t in 2011, 2012 is that it was too poetic and strayed from the central point. I thought I’d write poems with that in mind. I learned now that the two can be interwoven, but at the time, I was very invested in the writing of poems.

Why was that?

I didn’t think that I could write both. I was also not malleable about my poems, to be fair, so I thought that writing poems was just another career. It didn’t leave much time for the kind of whimsical music writing I was looking to do, which did not feel sustainable. Music writing felt like a passion project that I spent a lot of time on. Back then, I was freelancing for no money at all.

Another thing was that I wasn’t going to make any money doing either, so I decided to do the thing that I wanted, which at the time was poetry.

How did that feel when you chose that?

I was excited! I didn’t go to school for poetry or get my MFA, so a lot of my poetry writing was me figuring out poems on my own, and that was really exciting for me. That was a new entry point into the language I hadn’t experienced. And to have the kind of freedom to figure out what that meant for me and the possibilities of this new work I was opening up was really exciting.

Since you didn’t go to school for poetry, what called you to want to do it?

Columbus has a really good poetry scene with a lot of smart folks who are very talented. I would go to open mics and watch them read their work, and wondered if I could do it. Also, I started hosting a poetry open mic at this coffee shop around 2012, and they saw me writing there all of the time. It was one of those things where it didn’t make sense to not write poems, and I was excited to see what kind of possibilities were like in that realm.

When you started writing essays, did you start with music? Or did you write about another topic?

Music was always what I was writing about. I didn’t really know how to write about anything else, I guess. When I was young, I would write in a journal about music. As I got older, I had a blog about music that no one read. For me, writing about music is a personal act. I write about other stuff occasionally, but largely, my interest and focus is in music.

“I’m considering everything outside of just the songs and stage, and I think that makes for a world where everything happening has a place and everything is important.”

I know you get this question so often, but I have to ask: You’re an expert on a wide range of music. How did you get into all of these different genres?

I think both curiosity and a desire to search for things. I also grew up in a household where music was often, or always, played and that gave me a space to explore. My parents would listen to pop and funk and rock and soul. My siblings would listen to hip hop and R&B and grunge and metal. All of these things created a really strong blueprint for my musical interests. Not only that, they gave me an opportunity to explore on my own. I felt a lot of freedom to chase the sounds that most interested me, and not adhere to expectations of genre.

I noticed you’re very open about your anxiety disorders, your family, and your past. Were you always like that? were you always very open about things?

Probably not. I also think that I learned early on that I write a brand of writing that, again for better or worse, allows people into my life that makes them feel like they’re there with me. Like they know me.

There are parts of that that I don’t necessarily love, but that pushes me to be as open as I can be about the things that I now realize I’m not alone on, and that’s really useful. I also always think about myself when I was younger and how I often thought I was someone who was singularly agonizing over something when I wasn’t. To hear someone talk about how you aren’t alone is appealing.

Was there ever a turning point when you realized you could be vulnerable and open up to your readers?

Opening up serves myself in some ways too. By writing, it serves my desire to be an honest and pretty okay person. I didn’t really have a blueprint for vulnerability growing up, but I wanted to find one in my adulthood because it occurred to me that, particularly, straight men have to find some way to be responsible for our emotions or else we could weaponize them to hurt other folks.

How is your poetry writing process different from your essay writing process?

Oh, it isn’t. I don’t really think about genre too much when I sit down to write. I’m drawn to writing because I’m curious and I’m looking for a better way to articulate my curiosities. I’m often going to a page with the mindset of doing whatever it takes to achieve an answer to those curiosities. Along the way, something is built that looks like a type of genre, but I’m not interested in genre overall. Process-wise, I’m always looking at what will excite me or what will lead me to this end result that I’m looking for. Other times, I think of a page and I don’t know what [the piece] looks like or what I’m going to write.

I always thought that you went into writing, thinking, “Okay, so this is going to be a poem, and this is how I’m going to write it.” I love that you just start writing and it just comes to you.

Yeah, there’s something exciting about that for me, not really deciding what I’m working on before I work on it. There’s something really thrilling about letting the work just arrive as it does.

I think some people like to have a blueprint, but I like to write my way towards one.

With your music writing, does a song come to mind first when you start writing a piece? Or does the context or memory?

I’m always thinking of context or memory first. I’m always thinking about what can be attached to the weight of a song, a moment, or a concert. If you’re a big enough music fan, you’re not going to music only for the music. I’m always thinking about the full ecosystem of what the music provides.

At the Brooklyn Book Festival, you mentioned that you don’t keep a diary. How do you remember your thoughts on a certain topic?

I’m realizing now that I have a pretty okay memory. A lot of this stuff is just embedded for me because I’m always thinking about it. My brain is always storing these ideas and thoughts because they’re so tethered to my emotional state and my emotional mindset. There’s no idea that doesn’t have an emotional state tied to it.

It’s hard to imagine that any concept or idea that I want to work out is solely an idea. It’s also something that has a lot of emotional weight for me. It makes me hold onto those things closer and makes me want to be more responsible with the thinking process behind those things. It’s not only, “I have an idea and I have to get it down.” This idea leads me to some greater emotional answer, and so I have to present it internally.

There are also points where I say, “I don’t want to give this away. This is too precious to me and I don’t want to write it yet because I want it to be mine still.” A lot of this, for me, is what I can hold on to.

Your essays on concerts, like Bruce Springsteen’s and Carly Rae Jepsen’s, are always specific in detail. I was wondering, how do you prepare for them? How do you make sure you remember everything you saw while you were there?

I’m archiving a moment. I’m not just there just to be there. I’m there to take in what’s on the stage, and I also think that what’s happening off the stage is a really worthwhile thing to consider. I’m considering everything outside of just the songs and stage, and I think that makes for a world where everything happening has a place and everything is important.

I was rereading your book and noticed that you play around with the form in your essays. You said that you usually write and the genre comes to you afterwards, but with essays like “August 9th, 2014,” which was about giving up your seat on a flight, and “Death Becomes You,” which was an essay on My Chemical Romance that had five acts, it seemed deliberate. How did you come up with those formats?

If there’s one way I view poems and essays similarly is that the form, the way something looks on the page, has to serve the writing or the idea. For example, the essay that has the strike-throughs in it [“August 9th, 2014”], I was interested in the telling of two stories at once, and how that serves a particular narrative that I was reaching for. I thought the best way to do that would be to, on the page, actually tell two stories at once. Which is why, even though the words are struck through, they can still be read. There’s a vitality to that that was interesting.

I thought that My Chemical Romance, the name of that album and the theatric nature of it, to place an essay in acts was really useful. I’m always thinking about serving the topic and serving the idea. Those are two things that are really vital to me.

You’re about to release your book on A Tribe Called Quest. What about the group made you want to write a whole book about them?

I thought about rap groups that not only defined an era, but my entire life. A rap group that really opened a lot of doors and showed me a way to be a fan of rap. I thought that that was the more interesting book, where it’s a fan essentially giving thanks to a group or a band or an artist that taught them what being a fan was. Not only that, Tribe coming back in 2016 with an album, at least for me, was inextricably linked to the current moment we’re in. I was really excited for a book because it gave me a chance to come to those things on my own terms.

The book cover is inspired by The Black Keys album and Howlin’ Wolf. What drew you to those covers to use that style?

A thing we were running into with this cover was that there was a lot of text. The title is long, my name is long. Once we added the subtitle to it, there were too many words.

My first instinct was to take the title out and just have an image with no text on the cover, which obviously can’t happen. Any design that we used would be hampered by the text, and my thing was, “Why can’t the text also be the design? Why can’t the text itself be the art?”

I was also thinking about Virgil and Off White in some ways. I bought a pair of those sneakers and there’s something cool about the deconstructed nature of that style, where everything is taken. The shoelaces have “shoelaces” written on them, and shit like that, where everything is deconstructed. I thought, “What better way to do this? What better way to have this in the world than a weird deconstruction of what’s happening?”

I wanted to make the language artistic. It feels like there’s a little bit of levity to it, like it’s not very serious. In my head, at least.

One the flip side, for your cover for “They Can’t Kill Us,” how did you come up with that idea?

I wanted to pay homage to the rap that I grew up with. I couldn’t have a wolf on the Tribe cover because it wouldn’t make sense, but the joke about all of this is that I’ve wanted a wolf on every book cover I put out, which is another reason why the Tribe cover is at least an homage to Howlin’ Wolf. It’s my way of having a wolf on my cover even though I can’t.

I was fascinated with this picture from 1983 or ’84 that’s LL Cool J leaning on a car with a gold chain in that track jacket. I sent that picture and a picture of a wolf to my publisher and I asked if they could put the two together, and that’s what they came up with.

What about wolves draws you to them?

I’m fascinated by a wolf as an animal and its instincts. Wolves, by nature, are hunters. In some ways, their jobs are to survive at all costs. They seek out what they must to survive, and yet many species of them are going extinct. There’s something fascinating to me about an animal that is tasked with surviving at all costs and still cannot do it.

You also have a book coming out in 2020 about dance. What inspired you to write a book about that topic?

It’s mostly about performance. I wanted to write a book about black people performing, and I wanted it to be multi-faceted. Yes, it’s largely about dance, but it’s also about the more mundane aspects of performance that people don’t often imagine as performance. It’s all about juxtaposition.

There’s an essay about Michael Jackson and the first black man to walk on the moon. There’s a piece on Whitney Houston and soul train lines. All of these things that are placing one thing up against the other that I’m really excited about. I was thinking about how people imagine performance versus what I imagine performance. I imagine performance as showing up to a job you hate on a Monday.

With your book coming out soon, are you working on any other projects?

I have a poetry book coming out in October of next year. It’s not at all similar to my first one. It’s…different. It’s a book that deals in figuring my way through grief and heartbreak, while also understanding that no one owes anyone affection. No one is required to love anyone. It’s a book about my coming to terms with that.

Last question: Is there a story you’ve been itching to write, but haven’t written yet?

In the late years of her career, there hasn’t been a lot of writing on Loretta Lynn. I think it’s too late now, and I doubt that she’d grant one to anyone, but I had a long held desire to get a Loretta Lynn profile in. That would be a dream, largely because there has to be a point where we allow the elders to tell their stories before they’re gone, and before someone does it after they’re gone. The same with Aretha Franklin. She’s gone and now her story belongs strictly to fans and friends, and that’s great, but I would love to see a sprawling late-career Aretha Franklin profile. Or even a career retrospective, if she didn’t grant a profile. I’m thinking about ways to do that while bands or musicians are still here.

My brain is so much on Loretta Lynn right now. She released such a great album this year and a lot of people don’t even know that it happened. It might be her last album. She’s old and not well. It’s tough for me, because I think about how, when Loretta Lynn dies, how will she be talked about and how will that story be told?

I hope you get to write it at some point.

Yeah, at some point.

Hanif Abdurraqib’s third book, “Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest,” will be out in February 2019. His fourth, “They Don’t Dance No’ Mo’,” will be out in 2020. Here are his 12 songs:

What I always found most intriguing about this song was that I recall it as the first rap song I learned to love where the building of the song felt like a group activity. Surely ”Scenario” wasn’t the first crew cut I’d ever heard, but it’s the first one I remember and the first one I remember falling in love with. There’s something about the way the verses build upon each other that I didn’t hear everywhere else. The work of each rapper was to leave their own singular mark on the song. It felt like this really great group project with a bunch of friends. I felt like I had friends, so I could make a song. (I didn’t have that many friends and surely none of us could make a song.)

I hold London Calling in the highest regard as an album. It’s the Clash album that stitches together all of the intricacies in the varying sonic and political interests of Mick Jones and Joe Strummer, but beyond that, it’s a massive album which would be exhausting to take on if not for the fact that almost every song is perfect.

I have a couple of different anxiety disorders, and neither of them are particularly fun. There was a point in my life when they would be at their most treacherous when I was in grocery stores. There’s something about the unpredictability of a strange grocery store that was jarring for me. All it took was me not knowing exactly where something was, or seeing a shelf without a trusted product of mine on it, and I could easily spiral into a well of anxiety. First, about never having this thing I loved again, and then about who I might be letting down if I didn’t get the right chips for the party, and then about whether or not my friends liked me all that much in the first place.

I lived near this Giant Eagle for 5 years in my 20s and it was shitty, but it was my neighborhood spot. I’d learned the architecture of it really well, and so it was the only grocery store I went to. They never had much, but they had the few items I lived off of as a half-adult with no money. Cheap snack cakes, some decent hummus options, Simply Limeade. “Lost In The Supermarket” isn’t entirely about being lost in a grocery store — it’s this ode to how fucked up Joe Strummer felt living with his parents while being in one of the biggest bands in the world, but it was good to play that song while I walked the small handful of blocks to the grocery store that I knew well. It was a relief to hear someone sing about being lost and have it not be a prediction hanging over me.

“Pirate Jenny” is originally a song from The Threepenny Opera, and it is about a maid at an old hotel, fantasizing about getting revenge on the townspeople for treating her poorly. Nina’s version is not too far off from the source material, but it is slightly sparser. And, of course, the way her voice haunts is singular. It stops feeling like a showtune, and starts to feel more like the ominous retelling of a historical event. At the end of the song, a pirate ship with 50 cannons fires on the city and destroys all of it except for Jenny’s hotel. The Pirates capture all of the townspeople and ask Jenny what she wants, and she orders the pirates to kill them all, before riding away on the ship. When I was young, I heard Nina’s version while my mother worked around the house. It played on an old, crackling record, and Nina’s voice strained out every note. I swore it was about slaves, coming to get revenge.

I grew up with a lot of Miriam Makeba playing in the house, and I got very used to how effectively and brilliantly her songs weaved in between not just languages, but sonic aesthetics. I love “We Got To Make It” because of how it weaved into the mid-late 70s protest sounds of Black American music. It was the first song that I recognized as a song of protest and uplift, even when I was too young to fully understand those concepts.

The Love Movement was what I always thought the final Tribe album would be, until late 2016. Because of this, I’ve harbored a very real type of affection for it, even though I think most would say that it is far from their best work. But I love ”Busta’s Lament,” a song which felt like summer even though the album didn’t arrive until fall stepped through the door. I love Phife’s verse, and I always did. I had this on a cassette back in the day, and I’d play Phife’s verse and then rewind it. I knew exactly how long it needed to go before I could stop it on the start of his verse all over again. I’d get to the end, and then take it back, every time. There’s something special about that kind of labor, I think.

This song has kind of had a second life because of covers and samples. But I have always loved how it lived in its first life, as this kind of weird but catchy modesty anthem in the 80s. Also, Stewart is from Columbus, Ohio.

Devil Town is an unincorporated community in Northeastern, Ohio. It got its name because a tannery was established there in 1830, as one of the first things in the town. The residents couldn’t stand the smell of the tannery, and would have to get drunk in order to find some relief from it. The community got its name because when the people drank, it was said that they could become real devils, going over to neighboring communities and causing a lot of trouble. Now, there’s not much left of it except for a creek that runs through empty roads where the community used to be. I sat at the creek’s edge once and listened to this version of this song, Johnston’s voice straining through every note as if he were trying to fight out of the water himself.

This is as much an ode to home as it is an anthem for the world, and so it feels fitting to put this here. I’ve seen this song played live at least 15 times, and it never loses its resonance.

There’s the great moment when you realize that a sample has an entire life beyond the one you first hear it in. Mariah Carey’s “Fantasy” sounded so great when it dropped, but it also sounded too good to be possible. Even before I fully understood samples, I knew that song had to have come from another, even better place. I found Tom Tom Club before I found Talking Heads, which is wild. I remember finding that first album, with all of those weird ass tracks on it like “Wordy Rappinghood” and “Booming and Zooming.” I thought they were the greatest band.

I want to say here that I don’t think “Toxic” is the greatest Britney Spears song, and I’m often amazed by how that narrative has evolved over time and taken over the greater narratives in Britney’s career. “Gimme More” is great because it’s Britney doing what she’s made a career out of, better than she does anywhere else: stretching a song that is almost entirely chorus into something really rich and full, bursting at the seams. Blackout is such a uniquely great album of transition for her. One of the great transition albums of all time. She was fully grown and no longer in need of the public like they wanted her to need them. There’s something special that happens in that.

Sleater-Kinney is the most important American rock band of all time, and I truly mean that with everything in me. “What’s Mine Is Yours” is one of their great songs, and it relies on this kind of haunting and terrifying death-march of guitar noise and drums, starting at about the 2:04 mark. It feels heavier and more intense than a lot of the other shit I probably sold myself on as heavy and intense. It’s like a steady march to the gates of undetermined evil, right before Corin Tucker pulls you back right at the last minute.

I’ve got nothing here, but for what everyone else has already said a million times, I’m sure: Ray Davies is one of the great underappreciated songwriters of his era. I had this song on a mix that someone gave me in high school, and it was placed right in the #4 position on a mix, which is a highlight position — where the mix starts to transition from its introduction and get down to business. I never made it past this song. I still don’t know what else was on that mixtape.

Listen to Hanif Abdurraqib’s 12 Songs on Spotify.