Suzy Exposito brings her punk energy to Rolling Stone

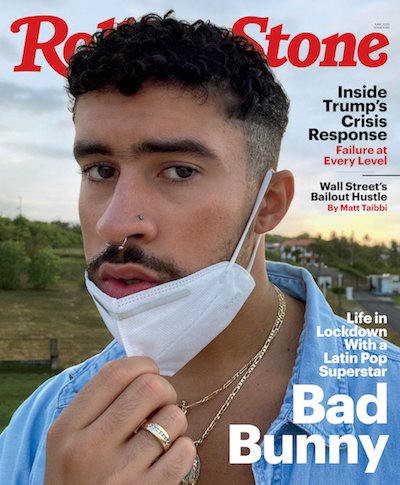

Suzy Exposito was supposed to be in Puerto Rico to shadow Bad Bunny a few months ago. But the pandemic hit and two days after arriving in Miami to interview the Latin pop star’s producer, Rolling Stone’s Latin music editor decided to stay put and social-distance at her grandmother’s house on an island within the city.

These thwarted plans, however, didn’t stop Exposito from becoming the first Latina to pen a Rolling Stone cover story.

“This is a dream come true for me — this is my first cover story. And it’s a dream come true for him. He’s always wanted to be on the cover of Rolling Stone,” she said. “We went in knowing that and being like, ‘How are we going to make this a fun, interesting story?’”

With the reporter in one island and the subject in another, Exposito and Bad Bunny adapted to the changing circumstances by keeping in touch the same way the rest of us are — by chatting over Zoom, sometimes for hours at a time. Turns out, that might’ve been for the best.

“We spoke for three hours last time and his publicist told me, ‘You got more out of him in a Zoom interview than you probably would have gotten if you were in Puerto Rico with him and his friends.’”

Exposito’s first foray in music journalism began when she founded a mixtape-sharing club in high school, which led to a gig as the Arts and Entertainment editor of the school paper. A self-proclaimed punk, emo, and indie snob, she later created a serial comic for Rookie Magazine, wrote under the tutelage of acclaimed music critic Jessica Hopper, and ultimately landed a role at Rolling Stone, where she’s been advocating for diversity at a publication that has a history of focusing on white, male-led rock and roll.

“That’s how I started covering Latin music at Rolling Stone — just by being really loud about it.”

We spoke with Exposito twice for this interview: the first, one month into the lockdown, and the second, two months after George Floyd’s death. Read on to learn about her nontraditional career path, activism work, and thoughts on what she’s learned from the Black Lives Matter movement.

. . .

You’ve said that you always wanted to be a rock journalist. Was there a specific moment that inspired that?

In the ninth grade, my friends and I used to hang out in the History classroom portable every morning. In Florida, portable classrooms are super common. Schools get overcrowded and when they can’t fit the students in the actual building, they add on portable classrooms.

My friends and I would get to school around 7:30 and school started around 8:10. The first place we would go to, because we had World History class in the morning, would be the History portable. Our teacher would be there, chilling out, and we would sit around and listen to music in the morning before class. That was when I founded the Mixtape Club.

There was a tape player in the classroom and I really liked making mixtapes with cassettes at the time. We started making mixtapes, bringing them to class, listening to them in the morning, and trading them. Gradually, word got around that the Mixtape Club existed and all of these older kids started getting in on it. We had a LiveJournal community and from there, I befriended the Arts and Entertainment editor at the school paper. He was a senior and was getting ready to leave [for college] and was looking for a replacement. He told the journalism teacher, “I know someone who would be really good at writing about music” and he recommended me.

I was 15 when I started reviewing records for the school paper. I was definitely an indie snob — at the time, I reviewed records by My Chemical Romance, The Strokes, Lily Allen, Amy Winehouse, Broken Social Scene. Ultimately, I was punk and emo. That’s where I come from, musically.

I guess you got a taste of music journalism when you were in high school.

Yeah, I would read Pitchfork every day, which is an interesting place to start. I would check out copies of Rolling Stone from my library and keep up with stuff that way. It’s interesting to see how these publications have changed over the years.

How did you go from being an Arts and Entertainment editor in high school to where you are now?

It’s not linear. I graduated high school and I started out as a Parsons student because I was studying illustration and writing, and I wanted to be a graphic novelist. I had my own web comic for a long time and I kept that up on Blogger and Tumblr. I then went to the New School in New York City for undergrad and majored in journalism.

In college, I tried to write for the school paper, but I was also actively involved in campus activism. [The paper] had this idea that you couldn’t possibly take a stand on anything if you wanted to be an “objective journalist.”

In the meantime, I was getting involved in punk and anarchism, and people would ask me to draw comics for their zines. The first one I did was “Not Your Mother’s Meatloaf” and it was a sex education zine. I contributed to that zine a couple times and thought, “Well, shit. I might as well do my own zines.”

I illustrated a comic called “Riot Grrrl Problems” and it was me sort of clowning on punk. It was about a girl in a band, trying to imitate the Riot Grrrls. There were a lot of hijinks and punk humor.

Then, I started doing more personal zines. I had a series called “Malcriada,” which is about growing up in an immigrant family. I had a zine called “The Mall Goth Chronicles,” which is also a Tumblr. I was actually archiving my diary entries from the time I was 13 until I was 16, during my peak goth and emo years. Once I was doing that, I got hit up by Tavi Gevinson from Rookie Magazine and she asked if I wanted to draw for the publication.

Through that, I was able to network with people. I started writing in the Music section at Rookie, and did some interviews, album reviews, and write-ups under Jessica Hopper. Eventually, she heard that Rolling Stone was looking for some diverse music critics. At the time, I was nanny-ing six days a week for three different families, freelancing at night, and playing in a band. I was already really busy, but I thought, “God, I can’t do this forever. This is really exhausting.”

I had a chance to prove myself, so Jessica put me in touch with Simon Vozick-Levinson, who’s now my editor at Rolling Stone. I’ve been writing there ever since.

What inspired you to create your “Best Song Ever” series for Rookie Magazine?

Tavi knew me from my “Riot Grrrl Problems” comics on Tumblr, but the thing about them was when I illustrated them, I illustrated them about white girls in punk. I was clowning on these stereotypical white girls in punk who are mean to people. Still funny and endearing, but the characters are not perfect by any means.

There was a character in “Riot Grrrl Problems” named Nia and she was the girl the main character would talk to on the bus. She was punk, but she was Puerto Rican. There was another character named Kiki who flirts with the riot grrrl at a dance. I decided, what if I take these characters of color and have them start their own band for this original Rookie Mag serial comic?

Exposito’s serial comic, “The Best Song Ever,” on Rookie Magazine.

That was basically what “The Best Song Ever” was: A group of girls of color starting their own garage band in high school. That was just so Rookie Mag to me.

You also recently illustrated a book! Tell me about that.

I’m finished! The author, named Stephanie Kuehnert Lewis, wrote a couple of books about punk girls before, like “Ballads of Suburbia” and “I Want to Be Your Joey Ramone.” She’s a young adult fiction author who lived through the grunge era, through riot grrrl. She lived in Chicago at the time when it was really popping off. She had a really wild adolescence.

She finally decided to write her own memoir about growing up in the 90s. It’s called “Pieces of a Girl,” but she wanted it to be like a zine and look a little fucked up. Who better to call than me?

It took about six months to draw everything. I was a little rusty because I’ve been a full-time music journalist, so I had to train myself how to draw again and how to draw things that I had never drawn before, like cornfields. There’s also research involved, so I looked at a lot of photographs of Chicago in the 90s to get the scenery. It’s the biggest project I’ve undertaken so far.

It’ll be the first book that I will ever publish under my name. Besides being a rock journalist, I’ve always wanted to be a graphic novelist. Even though I’m an art school drop-out, I’m really happy it’s something I can do.

When will the book come out?

It was supposed to come out in August, but because of the pandemic, it’ll be pushed back. We just don’t know when. Everything’s in limbo.

[Update: The official publish date for the memoir is March 30th, 2021.]

In your Songmess podcast episode, you mentioned that you were involved in punk, indie, and bluegrass bands in the past. How has being in those bands that aren’t under mainstream genres influenced the way you approach music criticism?

It’s been interesting, coming from a DIY background.

I will ask tough questions. I think any journalist should be able to do that without fear of retaliation. I still try to bring a confrontational punk energy to interviews. It doesn’t always go over well. Being a good interviewer is hard.

I write about Latin music full time, which was another interesting development in my career. I brought that confrontational energy to every meeting at Rolling Stone, being like, “You need to cover music in Spanish. It’s only getting more popular and the harder we ignore it, the worse we look.”

That’s how I started covering Latin music at Rolling Stone — just by being really loud about it, especially after “Despacito.” I thought, “You’ve gotta be kidding me. You cannot ignore this. This is not going to be the last time you see a reggaeton song top the charts” — and it wasn’t. For something like that, I’ve definitely fought to cover more marginalized groups in music and more marginalized genres.

And the thing about reggaeton is, it’s not even marginalized anymore. It’s a pop genre now.

It’s pretty mainstream now. Pop is evolving.

It is very mainstream and it’s been mainstream since Daddy Yankee’s “Barrio Fino.” And that was 2004!

It’s so bizarre to me, but this is just American Anglophone media. To even say reggaeton is marginalized in any way now is ridiculous to me because it’s everywhere. Working at Rolling Stone, which is a traditionally rock-oriented publication, I had to tap into that angry, riot grrrl, rabble rouser energy to make sure that Latinas were being heard because you hear us everywhere in New York. You hear us in bodegas, in your taxicabs — you hear us everywhere. Why isn’t that being reflected in music media?

Another really important part of my job is not just shining a light on Latinas, but also making sure that we have the right to be mediocre and make crappy music that’s worth criticizing. I love my people. I love us enough to know when shit sucks and I’m not afraid to say that.

On the flip side, as one of the few females of color at Rolling Stone, do you ever feel pressured to cover certain topics?

All the time. When the “American Dirt” controversy happened, several of my coworkers said, “Suzy, you should totally write about this for Rolling Stone,” and I was like, “No, I shouldn’t.” Just because I’m the only Latina on staff doesn’t mean I should have to be the voice for all of these things. There are plenty of freelance writers who could do that topic justice.

While practicing social-distancing, you’ve been working on your own music. How is that going?

My best friend from high school and I used to have a dinky little band in high school called The Kites. We used to record silly songs all the time. Since the quarantine began, he reached out to me with a couple of demos and said, “I think I want to do something with these songs. If you want to sing over them, please be my guest.”

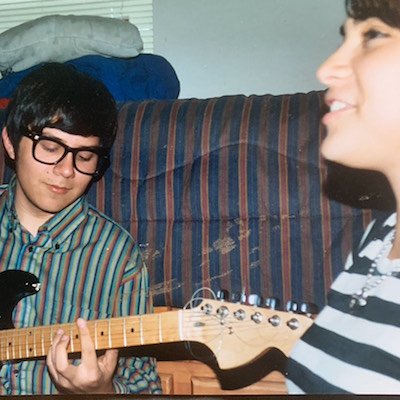

Andre Grüber (left) and Exposito (right).

One of the songs is a pop-punk song. He sent me the guitar and snare drum track for it, and I went into my nana’s living room closet, put pillows at the door to block out any sound, and recorded the vocals. I wrote the song in thirty minutes, recorded it, and sent it back to him.

We haven’t agreed on a band name yet, but the first song we did is called “Drive Me Down the Coastline (Tell Me You Love Me),” like a Taking Back Sunday song title. We might make a Bandcamp, but I don’t see us going as far as putting our music on Spotify or trying to make any money off of it. I just like that it exists.

The country’s been on lockdown for a while now and artists are canceling their tours or pushing their album debuts back. How do you think the music industry will change after the pandemic?

I think it’ll change a lot after this. People are going to have to figure out how to monetize these digital concerts.

Part of going to a concert is the communal experience of being around other people and experiencing it live. It’s unparalleled and it scares me to think about how long we have to go without it.

Concerts have increasingly become the bread and butter for most artists, especially given the fact that not as many people buy records. The way that Spotify compensates artists is extremely unfair and a lot of artists have had to rely on touring to make any kind of livable income, if even livable.

It’s also been dire for independent venues that aren’t owned by AEG or LiveNation, and it was hard enough for them to run even before the pandemic. An interesting thing I’ve seen happen is that a lot of these venues have Kickstarter or GoFundMe accounts that people are donating to, so these places can keep paying their rent and will still exist once the pandemic slows down.

I would definitely encourage people, if you enjoy live music, to find out if your local music venue has one of these fundraisers. If you want to start one for your favorite venue, please do so.

It’s looking scary now, but I think we can help stave it off.

A month after we spoke, the death of George Floyd sparked Black Lives Matter protests across the world that are still continuing today. As the pandemic loomed, the U.S. was (and still is) grappling with its inherent, systemic racism as people held its communities and governments accountable. Mainstream media’s lack of diversity was also shoved into the spotlight, a byproduct of the movement.

We followed up with Exposito to get her thoughts on the current climate.

How does it feel to be back in New York City?

It’s great, I am glad to be back. I’ve heard two protests outside of my window, today alone. Don’t get me wrong, the fear of the virus is definitely palpable, but I am excited that the Black Lives Matter protests are back. I took part in the first round several years ago, but it’s good to see people back and engaged with it. It’s horrible to see that a lot of these problems never resolved themselves the way that we would’ve liked, but it doesn’t happen overnight, so being back has put everything in perspective for me. After spending three months with my very elderly grandmother, I was kind of living in a bubble.

You’ve been an activist for a long time. What are your thoughts on the current iteration of the movement?

It’s really hard to say because I’m not a Black person. I’m specifically a non-Black Latina, and so I want to preface by saying that anything I say doesn’t come from a place of wisdom, even though I’ve organized protests before. I can’t offer any authority on the movement.

However, what I think is so heartening this time around is seeing how many more people are engaged with it. I was involved in Occupy Wall Street in 2011 and by that point, I had been organizing for a couple of years. After Trayvon Martin was murdered in 2012, I remember how important it was for people involved in Occupy to also understand why it would be important to align with the people organizing Black Lives Matter protests. I feel the same energy coursing through these protests, people understanding that every act of violence that they experience is not in a vacuum. It’s part of a larger system that permits this kind of violence to proliferate across society. And so, I feel my role is so much more different now.

Right now, I’m thinking about how I can reasonably be helpful to the Black people in my life and not in my life. It’s important that we’re all expanding our social networks, expanding what it means to care about people. I see a lot of people confronting the fact that maybe their social circles are not as diverse or as expansive as they would have liked or as they thought they were. People are coming to grips that their workplaces aren’t very diverse. That’s no mystery to me, working in media.

This is a time for all non-Black people to examine the role that race plays, specifically the role that anti-Blackness plays, in everything we do. A lot of us have to do more homework on how anti-Blackness has shaped our lives and how we’ve come to benefit from it. And for me, I’m just talking to people a lot. I didn’t participate in any protests because I was quarantined with my grandmother who recently recovered from cancer. It just would not have been smart or safe for me to potentially expose myself, come back, and possibly give my grandma Covid.

Have you learned anything new this time around?

The first time I went to a Black Lives Matter protest, most people in my circles were white because I went to a private college in New York City and most of my friends were fellow students. We were all being prompted to work on each other and work on our friends if they’re not quite up to date about racism, but I felt like that was an easy way to skirt my own issues with anti-Blackness. I grew up in majority white spaces and so I felt, for a long time, that I was exempt from a lot of these conversations.

Now, the time comes for me to specifically talk to Latinx people. I can’t believe how long it took me to finally confront the fact that I had done and said and thought racist things in my lifetime. I didn’t think I was completely exempt, but I didn’t think it was bad. I just always understood white people to be the primary aggressors of racism, and because people had been nasty to me in my life and created barriers for me throughout my education and career. It didn’t mean that I could have done the same thing to any Black people in my life.

For a very long time in this country, Black Latinos have been systematically marginalized in media and culture. They have experienced the same aggression as African-American people in this country, in Latin America. And even though a lot of people in Latin America are mixed, it doesn’t give us any license to compare our struggles to that of Black people.

“There is the same social stratification in Latin America as there is in the U.S. because of colonialism. Latin America was colonized the same way North America was colonized — they have very similar legacies. The only difference is who the colonizers were.”

I have known and grew up with the same mentality that Latinos couldn’t be racist and when compared to Americans, we’re an exception when it comes to racism. That is such a myth. The last two or three weeks, I’ve been talking to people in my family, talking with people in my life about how to honor the Black people in our lives and their contributions.

My family is mixed: my mother is Belizean-Creole and mestiza. My grandma is visibly Black and indigenous, and has siblings who identify as Black or mestizo. My grandfather is English, Irish, and Spanish from Belize. And my dad’s family is Cuban, but very much Spanish. They are white Cubans — very European-looking people — whereas my mom’s family is a lot more mixed. I have cousins who identify as Black even though they’re light-skinned. For the longest time, I thought I couldn’t be racist against Black people because after all, I have a grandma I love who is Black or uncles who identify as Black. I just didn’t think it could happen to me, but I never experienced a lot of the things that they experienced. Now, a lot of Latinos are having the same epiphany.

I’m confronting anti-Black racism in my culture, in my community, and actually trying to talk to other non-Black Latinos about it because we grew up with so many misconceptions. This is the time for us to be in solidarity.

The last time we talked, you spoke about how Rolling Stone wasn’t really diverse in its music coverage. What are your thoughts on the current exposure of publications and their lack of diversity?

Rolling Stone, until recently, did not have a very diverse staff for a really long time. It’s only the last couple of years that they made a more concerted effort to start hiring more people of color. There was a time when I was the only Latina. The thing is, before anyone can get mad at me for saying this, that is New York media.

It starts with the culture that gate-keeps and requires people to have degrees from elite universities, which often require a lot of money to begin with or require us to take out enormous student loans, like I did. Before you get to the point where you get a job in media, there’s so much working against you if you are a person of color in the United States, especially a working class person of color.

The reason why I started going off about racism in Latin America is because right now, the Latin music industry doesn’t know what to do. They are so lost. Because of this mentality that I described to you, I think that institutional racism and anti-Blackness is very much alive in Latin media.

“We have a lot of the same problems in the Latin music industry as they do in the Anglophone American music industry. It’s just in a different language.”

The thing is, those of us Latinos living in the United States are marginalized. Even if they’re white, some people have very Spanish, ethnic names. That alone can be the deciding factor in whether someone treats you like shit. Because a lot of non-Black Latinos experience barriers to success in many industries in the United States, it’s really hard for them to grasp the ways they also hold Black people back. They way they marginalize Black Latinos, especially.

Right now, it’s kind of a come-to-Jesus moment in the Latin American music industry. People are having really interesting conversations. For me, I’m dedicating more time to covering more music by Black artists. That’s something I was conscious of when I started Rolling Stone’s Latin section. I have to be more critical when curating my section. Even then, it’s never really enough.

You mentioned that Rolling Stone has bee trying to be more diverse in staffing. Could you talk a bit more about that?

I think in the music journalism world, that is definitely something more people are starting to warm up to. When I started writing about music professionally in 2013, that was the conversation that had yet to be had. A lot of us were talking about women getting hired in these publications. Women were still a novelty for a time. It was like the fucking Smurfs — every publication had their Smurfette.

Now, I can see the same sea change happening when it comes to hiring more critics of color. I’m just glad that the heat is on because it was a long time coming.

Here are Suzy Exposito’s 12 songs.

Though it’s probably 15 years too late, I think emo kids deserve a teen movie — loosely based on my life, obvi. For my 12 Songs Playlist, I've curated an imaginary soundtrack with some of my favorite songs from my teen years, both emo and emo-adjacent, and the real-life, emo-as-fuck moments they take me back to. (Side note: this playlist was written under the moon in Pisces trine Mercury retrograde.)

This was my fucking anthem in high school. I used to go out of my way (or rather, take to Livejournal) to find emo/punk bands fronted by women. My friends would make fun of my militancy for listening to music by women, but in the 2000s, during the reign of Warped Tour, women were really fucking struggling to be heard amid the din of commercialized, white male discontent. I was a walking billboard for Gen X bands like Bikini Kill and Sleater-Kinney, whose logos and lyrics I scrawled in puff paint on T-shirts.

I feel like Pretty Girls Make Graves was one of those bands for my generation — angsty girls too young to catch the riot grrrl wave, girls who liked our punk mathy and angular. I loved how Andrea Zollo could articulate a conflict between women without resorting to misogyny (“If You Hate Your Friends You’re Not Alone”) or sing wholesome songs about falling in love with music (“Speakers Push the Air”). Good Health may not be a canonically emo album, but it’s one of my top five emo albums of all time.

The first time I’d ever heard At the Drive In was late one night at my dad’s house in Miami, the summer before 7th grade. I liked to stay up and watch MTV’s alt-rock video show, “120 Minutes,” which at that point, had only aired late at night on MTV2. One fateful night in 2001, they played the chilling video for “Invalid Litter Dept.,” which first educated me about the femicides in Ciudad Juárez (which borders ATDI’s native El Paso). It was probably the first time I’d personally seen a rock band challenge violence against women, and especially against Latinas — something many Latinx artists remain silent about in 2020. It rocked my world to see Latinos play in bands like ATDI, not to mention Deftones, Rage Against the Machine. Paz Lenchantin from A Perfect Circle inspired me to pick up the bass. But "Invalid Litter Dept." became my entry point to the world of emo and post-hardcore, and I really couldn’t think of a better place to start.

When it comes to dating, I started pretty early; I had my first steady boyfriend when I was 13. He was a white Southern boy with blue eyes and a love for metal. Having just moved from Miami, where Latines were the majority, to Jacksonville, where I was suddenly the minority, my new crush seemed totally exotic to me. We spent six months writing each other love poems, making out after school and talking on the phone most nights… until his dad sent him to military camp in North Carolina to “man up.” That summer, my boyfriend began parroting some of the worst white supremacist rhetoric over the phone with me. At some point, he said he didn’t know if he could date a “foreigner” like me (a U.S.-born Latina), that I wasn't as pretty as my white friends, and that I needed to go back to my country. “Then go back to Europe, you fucking idiot,” I said.

I hung up on him, made out with some kid at day camp that week, then made a breakup mix titled “You’re So Last Summer.” It’s hilarious to me now, but the experience negatively impacted the way I perceived myself for many years.

There's no deep story or analysis to this song. I just always thought it'd be great for a "first day of high school montage," even if not mine! In reality, I was still transitioning out of my nü metal phase on the first day of high school. I recall wearing a red plaid mini dress, platform boots and a messenger bag with a Slipknot patch on it, but I secretly listened to SoCo on the bus rides home, just wishing for a garage band king to sweep me away.

In the summer of 2004, four major hurricanes ripped through the state of Florida for nearly all of August and September. The power was out, school was canceled for the first two months of 10th grade, and my neighborhood was covered in fallen oak trees. I was completely devastated — not at all about the hurricanes, but about a crush who dressed like a Stroke and stopped answering my phone calls. We miraculously came back to school for two days on the week of my 15th birthday — during which I threw my own punk rock quinceañera in the courtyard, donning a white fluffy dress, tiara and combat boots. I was so ready to bounce back!

But then after weeks of ghosting, my crush cinematically, and almost cruelly, appeared to wish me happy birthday. In spite of my tough, Courtney Love veneer, I later wrote in my diary, he made me feel as though "my body had turned to glass, and he was fixing to break me." I went home and I listened to this song as my therapy; I found a home in the fragile quiver of Caithlin de Marrais’ voice, tapering off as she sang the lines: “And I’m certain if I drive into those trees/It would make less of a mess/Than you’ve made of me.”

I can’t think of this song without thinking of a scene that I once documented in my Livejournal: my Cuban father and I in the car, somewhere in Miami, 2005. We pulled up at a stop light next to a car full of boys with scene bangs and black tees. When they saw me, they rolled their windows down and began to serenade me with this song. “Where is your boy tonight? I hope he is a gentleman,” they sang. I was beaming; my dad was seething. “Look at them,” he scoffed. “They got skinny arms, their hair’s in their faces. What a bunch of pansies. Your generation is weak!” Right on cue, the light turned green, and the scene boys sped away, headbanging into the Florida sunset.

Mike Herrera is an unsung pop-punk genius. I find it fascinating that MxPx didn't get the same level of fanfare as bands like Blink-182 or NOFX, but I think it had a lot to do with their origins as a goody-goody Christian punk act in the 90s. "Begin to Start" is the most purely MxPx song I can think of — it is the nexus where their jazz, pop-punk and doo-wop influences convene in blast beat reverie. If I was coordinated enough to be a skater girl, which I am in my fake teen movie, I would make one hella dramatic skate video to this song.

The most famous pop-punk/emo band out of Jacksonville may have been Yellowcard — who, like me, attended Douglas Anderson School of the Arts — but my favorite was Emergency! Action Boys. As North Florida's answer to Braid, Emergency! Action Boys were one of those hidden gems you only discovered by word of mouth, or in my case, a mix CD from a cool older friend. That kind of music discovery is such a rarity now. I was feeling super nostalgic last year, thinking about listening to that CD in my friend Nick's car after school, the day he drove us to the beach with his bare feet on the steering wheel (chaotic teen boy shit.) When I Googled the band, I was pleasantly surprised to find their music was uploaded to Youtube, 15 years later. I listened to them and thought of the ocean.

Ever fallen in love with someone you shouldn't have fallen in love with? Namely, your best friend?

My best friend Andre and I met the very first week of high school. He immigrated from Caracas, Venezuela to Jacksonville. I noticed he was wearing a Melvins hoodie, so obviously I chose him, like a Pokémon, to be my BFF. We took the same bus to school every morning and listened to music in the back of the bus, singing along to everything from Daddy Yankee to Iron Maiden; but the band that we both loved most intensely is probably My Chemical Romance. For months we shared earbuds and sang "I'm Not Okay," almost every morning, to the great annoyance of our peers.

It was finally during our senior year that Andre and I caved to our romantic curiosity for each other. It didn't last very long; I found him to be very traditional in ways that I was trying to resist, as the college-bound eldest daughter in a family of immigrants. But his parents LOVED the idea of us together, and Andre began sharing fantasies of us getting married and starting a family. At 17, the prospect terrified me! So after three fleeting months, I finally blurted out that I wanted to break up. Thus began Andre and I's elaborate six-month feud straight out of “Rebelde”: I dated some doofy skater boys who were more my speed, and he dated my nemesis. Three cheers for sweet revenge, indeed!

No joke: Andre broke up with my nemesis on the dance floor at prom night. I actually saw it go down — the two of them sparring with each other in formalwear — while I was sipping ginger ale and dancing with my date to "Laffy Taffy." Andre and I made up after that, and we still laugh about it to this day, but it was truly the most “Rebelde” shit ever.

On a related note: I'm honestly shocked and offended that Straylight Run has not been given the teen movie soundtrack treatment. The violin rock? The dueling male-female vocals? This title alone, my God! Justice for Straylight Run!

In the mid-2000s, just as emo started getting more scene (read: more hair metal), I had begun to tap out and lean towards the indie snob end of the spectrum. I've only seen a handful of episodes of “The OC,” but I enjoyed the music supervision on the show. One of my favorite “OC”-core bands was Pinback — there is this subtle melodrama to their music that feels so unmistakably emo to me. In that time I began my descent into LiveJournal and Myspace addiction, desperate to follow my friends' more "exciting" lives while my super strict parents kept me at home most weekends. It was upon revisiting Pinback during quarantine, which felt much like those years under parental lockdown, that I realized how prescient their music was. Songs like "AFK" (“Away From Keyboard”), and earlier ones like "Offline P.K.," described a generational communication breakdown, unfolding under the influence of the internet, and deepening our alienation from each other. ("Seldom to touch, far away from here/Even if I'm released/I can't talk to you anymore/And I miss you.") 2020 is 2004 is 2001.

… then came the great pandemic of 2020. Andre messaged me one day in March asking if I felt like writing a pop-punk song with him. He was bored at home in Jacksonville, and I was working on the Bad Bunny Rolling Stone feature at my Nana's apartment in Miami. The song quickly became a work of concept art; a generic emo song we might have written together in 2004, had we been more musically and emotionally literate. Andre recorded the guitar and drums, I recorded the vocals in my Nana's closet, with only pillows and blankets to soundproof. The video was entirely produced and shot by me on an iPhone, while running around the tiny, scenic neighborhood of Treasure Island. Yes, I picked my own song for this, and I'm definitely not sorry!

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to 10 of Suzy Exposito’s 12 Songs below: